Two More Books!

- Nov 30, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 6, 2024

Volume XXIII, Issue Five | Dec 2023

I thought when Where Coyotes Howl was published, I was finished writing books. It’s not that I wanted to stop, but I was out of ideas. And I was getting older. There was something nice about getting up in the morning and knowing I wasn’t under pressure to write. But that was scary, too. If I didn’t write, what would I do? It’s not that I played golf or have hobbies. My whole life has been about writing.

I had sent a draft of a book, The Hired Man, to my agent, but I wasn’t satisfied with it. She wasn’t either. Neither one of us knew what to do with it. Then one day, she called and said her assistant had read a manuscript I’d written a dozen years ago, called Finding Pa. She loved it. When she read it again, my agent loved it, too. Neither one of us could remember why it had been put aside, but we think I’d started on A Quilt for Christmas and never got back to Finding Pa.

The upshot was St. Martin’s bought both Finding Pa and The Hired Man. I’ve finished the editing on Finding Pa, and now we’re moving on to the copy editing stage, cover design, finding blurbs, and all the minutia of publishing.

One problem was the title. My editor thought Finding Pa sounded like a children’s book. But Finding Pa had been the working title, and I had no ideas for another. Neither did my editor or my agent. Then last month, I went to New Orleans, and while there, told my daughter Dana about the title dilemma. We were walking along one of New Orleans’s terrible streets, and she explained that she and her neighbors had bought a truckload of gravel to spread in the mud in front of their houses. That’s when she suggested The Road Less Gravelled. Then we got serious, and a few minutes later, one of us—I can’t remember who—came up with Tough Luck. And that’s the new title of the book.

Tough luck is different from my other books, which have been filled with heart-breaking episodes. It’s funnier and more lighthearted. My agent compares it to True Grit. Tough Luck is the story of two “orphans” who go west in 1863 to find their father. Now that their mother is dead and their brother has taken off to become a riverboat gambler, Haidie and her brother Boots, decide to escape from the orphanage where they’ve been dumped. The book is filled with adventure, quirky characters, and there’s even a con game. Tough Luck will be published in early 2025.

Now that I’m on a roll, I may even attempt another mid-grade book.

“Sandra Dallas” Tree

The Douglas County Libraries are featuring a forest of Holiday trees dedicated to writers from Edgar Allan Poe to Janet Evanovich. This year, the Highlands Branch set up a “Sandra Dallas” tree with book covers, quilt squares, tiny bouquets of flowers and hand-made ornaments of log cabins my characters lived in. Instead of a star on top, there is Povy’s photograph of the Bride’s House. The tree is one of the nicest honors I’ve ever received, especially since many of the ornaments were made by library volunteers. Thank you Lisa Casper and all of you who dedicated so many hours to the tree. (Confidentially, it’s the nicest of all the trees there.)

Will Rogers Medallion Award

It’s been a good year for recognition. Little Souls won the Colorado Book Award in June, and in October, Tenmile was named a finalist for the Will Rogers Medallion Award. The award was created to recognize quality in cowboy poetry but later was enlarged to recognize western literature.

I couldn’t attend the ceremony in Ft. Worth and assumed I hadn’t won. Then when I opened my mail after I returned from New Orleans, I was thrilled to find a huge gold medallion. Tenmile had taken first place in the Western-Fiction-Young Readers category.

Sandra’s Picks

For a long time I knew Denver writer Harry Maclean was working on a book about Charlie Starkweather, the first modern-day serial killer. I was a teenager when Charlie, accompanied by his girlfriend, went on a murderous rampage across the West, and I remember the fear his name engendered. I even remember, after he was captured, the controversy over whether his girlfriend was a participant in the murders or a kidnap victim. This was before anybody talked about the Stockholm syndrome. Maclean grew up in Lincoln, Nebraska, where Charlie lived. His brother went to school with Starkweather. The author doesn’t just recount the story of the psychopathic killer but delves into whether the girlfriend participated in the murders. I was so impressed with the book that I’m including my entire Denver Post review of it:

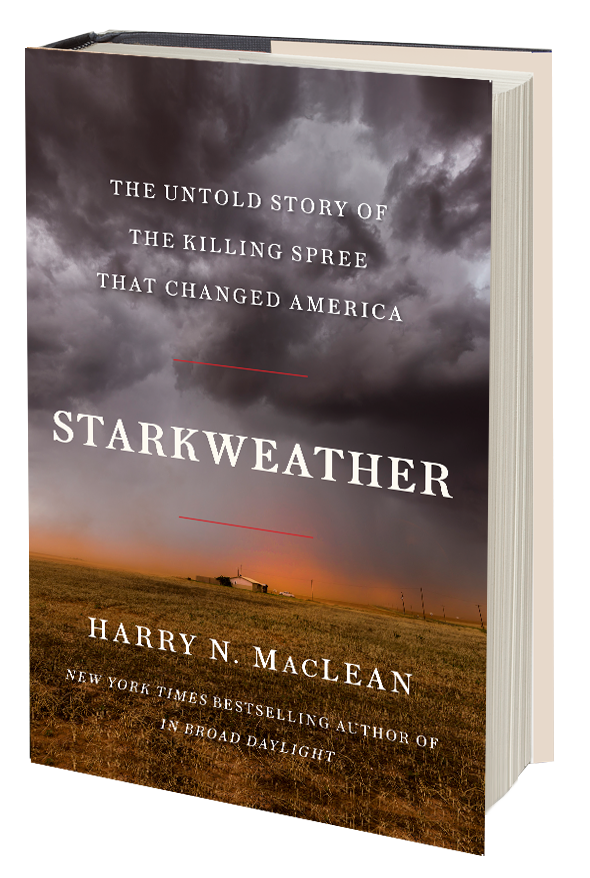

Starkweather

By Harry MacLean Counterpoint

Even 65 years later, the name Starkweather brings chills. Charlie Starkweather, 19, accompanied by 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate, murdered 10 people in six days. He was America’s first contemporary mass killer, a psychopath who thought of himself as an outlaw and dreamed of going down in a blaze of glory in a shootout with the cops. When he was captured instead, he said he dreamed of being put to death in the electric chair with Caril on his lap.

For Caril, that was a nightmare.

The red-haired, bow-legged Starkweather, who affected a James Dean look with a cigarette dangling from his lips, started his killing spree in Lincoln, Nebraska. He murdered Caril’s mother, stepfather and baby sister. Then, with Caril at his side, he killed a farmer friend, two teenagers who stopped to give them a ride, a Lincoln couple and their maid and finally a motorist who was taking a nap in his car. (Prior to these killings, he had murdered a gas station attendant, later saying the killing had made him feel good.)

The murders terrified Lincoln (and embarrassed the town even to this day.). Schools were closed, people locked their doors for the first time, men took out their guns. Across the nation, people were fascinated with the teenage killer. He was featured night after night on the Huntly-Brinkley Report, written up in “Time” and “Life” and covered in national newspapers. People nationally turned on the radios to find out if the couple had been captured.

Starkweather freely admitted he was a killer. The question was did Fugate participate in the murders with him, or was she just a captive, forced to accompany her boyfriend on his murderous rampage? Caril insisted she didn’t know that Charlie had killed her family. She claimed he told her they were being held captive in a secret place by his “gang’ and would be killed if she didn’t do as she was told. Skeptics, however, pointed out that Caril had numerous opportunities to escape. Most people in Lincoln, prodded by biased reporting in local papers, insisted she was as guilty as Starkweather. Seventy years later, they still believe that.

Charlie claimed she was, for that matter. He was vengeful when he found that Caril had turned on him, calling him crazy. She’d spoiled his dream of their dying together, Charlie, the fearless outlaw with his gun moll by his side. So he testified against her. His word, in fact, was the only real “evidence” the prosecution had against Caril. Still, she was found guilty of first-degree murder. Just 15 years old, she was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Any number of books have been written about Starkweather and Fugate. Now, Harry N. MacLean tackles the subject with a meticulously researched book that questions Caril’s involvement. The Denver writer, author of “In Broad Daylight,” the Edgar-Award-winning book about residents of an Iowa town killing their town bully, sets out to determine once and for all whether Caril was really guilty.

Caril was just 14 during the killing spree. “A brain of an adolescent girl is more developed in the right side or emotional part of the brain than the left. Caril said she was scared for the lives of her parents...” MacLean writes. He counters the idea that she should have taken advantage of chances to escape with, “What was the girl supposed to do? Charlie “held a gun on her and threatened the lives of her family…take her father’s .410 and shoot Charlie while he lay asleep in her bed? Simply walk out of the house and down the street? And go where? The police station? And tell them what? And risk, however improbably, the lives of her parents and sister.”

Caril operated under trauma-induced duress, MacLean contends. But this was the 1950s, and people didn’t care about the workings of the adolescent brain. Conditions such as Stockholm Syndrome hadn’t been identified. Despite her age, Caril was tried as an adult. The judge seemed to side with the prosecution, and the jurors had access to opinion in the daily newspapers.

Most shocking of all, the primary evidence against her was Charlie’s testimony. He’d originally told lawmen that Caril had nothing to do with the killings. When he found out Caril wasn’t going to plead guilty so she could be put to death with him, Charlie changed his story.

If Caril were to be tried today—and that is a big if, considering the lack of evidence—she’d never be found guilty, MacLean contends.

Starkweather is a blockbuster of a book, hard to put down, although in places it is tedious with its repetition of facts. The stunning ending alone is reason enough to read the book.

The author’s prodigious research and his conclusions shed new light on both Charlie and Caril. He admits “The question of Caril’s participation in the killings…will likely not be settled once and for all.” Starkweather will only add to the controversy. Charlie Starkweather wanted fame. Caril didn’t. But both of them got it beyond Charlie’s craziest fantasy.